where do you

want to go?

this was posted on

07-20-21, tuesday.

an idiot's move

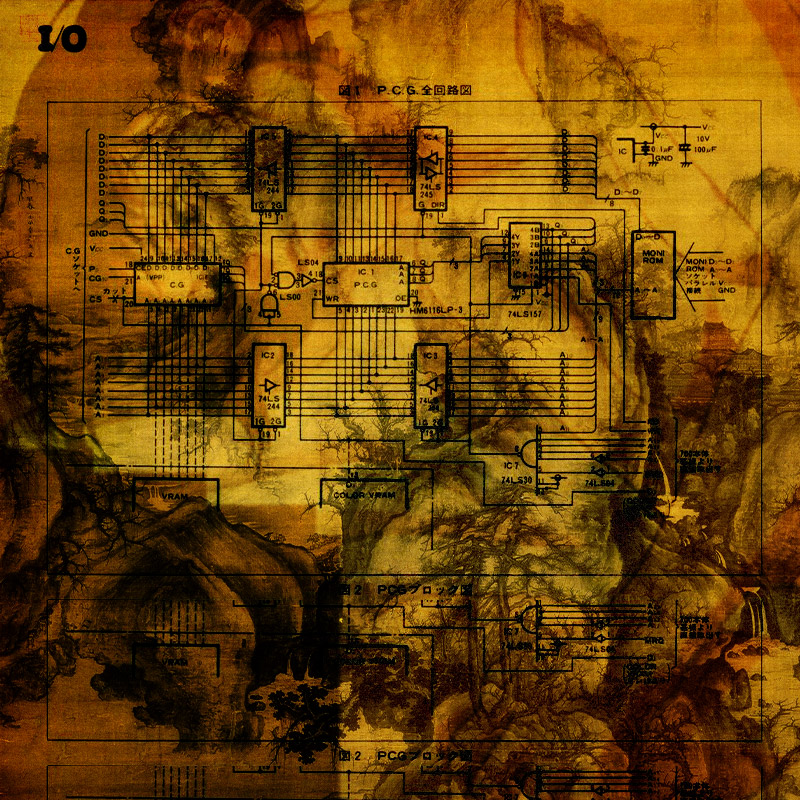

it is unclear to me whether the amphetaminic spasms of modern variety shows are for to dissuade the watcher from latching onto an immanent hopelessness, or are the only white noise in which it is possible to live slow

Why did you have to wait until we were alone?

...

Why didn't you tell me you were drunk? Why did you drive home drunk? If you had blurted it out in front of everyone it wouldn't have felt so bad, I could have denied everything, or yelled at you, or left, but you slipped it in privately, all knife-like and slow, like it was a mercy ...

June—

I wouldn't have had to see you again—I probably would have never spoken to 野村 even, would have ghosted his texts, hard, and left this resort town and gone and been silent somewhere else beautiful. Harmless and neutered somewhere else. And then small disasters like your comment occur and it becomes so obviously clear that I am not as skilled at being immune and cryptidinous as I think I am; that I am in fact very visibly open and my underbelly is soft and white and pregnable and the people around me have always already been aware of my insecurities—my lack of ability to execute and inpugn and punish. I am harmless. But worse than that I am deluded about my ability to cause harm when I want to. I am like bismuth or baby aspirin. It is not even about you—you are like a hollow thing from which this effluvium has poured and pooled and poisoned my dreams, or something, and my realization of this is exactly the same as an identification of this excretium with me—as "produced" by me and within me as in the "production" of bile. It's all over me and disgusting. And it's so clear that it will ultimately kill me in the same anorexic mode of Alzheimer's or certain slow sarcomas.

June, I'm right here.

And.

And you're being cruel. It's an idiot's move. That paragraph was, somehow, self-punishment in the shape of a scalpel cutting into me. I'm right here. Use words I know.

I'm saying it isn't your fault.

Can I drink some more of this water?

Stop asking, please—for the love of God.

You left this water for me.

...

You walked over to the tap and filled it up, an inch from the brim, and placed it far enough away from my head that I wouldn't roll over and knock it over.

...

...

I didn't sleep at all.

I slept soundly.

I don't get insomnia though—I have slept through horrible contingencies and scarring occurrences. You honestly wouldn't believe half the stuff I could tell you. I think this says something bad about me, I am almost certain it means something terrible, and yet I still sleep well, even knowing that I am obviously fucked.

...

...

I called you a liar because you were being one.

And that's supposed to make me feel good?

...

...

I don't know you, June—it was supposed to get you to say something that wasn't a joke or an insult or overwhelmingly élite. And so far it has precipitated a long list of poor attempts. Why does it feel like everything is worse than it is, around you?

...

...

I'm sorry.

It sounds painful. To feel pain that way. Do you get what I mean—your experience itself, beyond of any actual pain involved, seems itself awful. Nauseous. It sounds painful for you to live in sight of yourself, constantly, like that.

...

June, it sounds like it hurts you to speak.

...

...

That's why I don't talk much.

...

...

There, I finished the water—would you like to get coffee somewhere?

...

It's okay—I know a place way out of town.

...

...

...

What are you writing?

>>>

Muffled sounds of マリ shaking out her jacket, the futon, rinsing her face in the mini kitchen's sink and spitting. In the bathroom alone I see I have sheet marks on my cheek, which extend down my neck, curl under an armpit, and terminate on the opposite thigh: a red embossing of brocade flowers and beadwork. I am dehydrated—if I stood still enough I might be able to prevent my body from refilling these nibbles taken out of it: shallow lenticular depressions in my skin. I brush my teeth and spit deeply, leaving a small spearmint bolus. I finger-comb my hair.

Weak coffee in featureless white mugs while incumbent in vinyl-covered booth seats. The coffee's thinness is good, as if it had been known that this was exactly what I needed, like it had been prescribed or theorized. Much of this feels that way—as though by the direction of a calm ulterior power. A plate with a tall flaky croissant and pain au chocolat and another pain au chocolat, meaning we rip the croissant down the middle and share it. Butter wafts. Common everyday items exist instead as the actions to be taken in relation to them, and these actions simply occur. Conversation is happening: names, weather, siblings, animals, travel, apocalypse & eschaton. A low-volume CRT television suspended by a dull bracket up in the corner hums thickly, watched occasionally by the waitress, who has very little to do. Small faces in boxes on the screen, which is itself a box with larger faces. A "variety" show. Sizzling from the back kitchen. Toast and muscat jelly in small blister packs. The chairs face the windows which face the sea.

マリ's most recent boyfriend had grown up on the eastern coast and had been sixteen when the next town over was destroyed by the water. Unclean. His only connection to the town had been a girl he had been dating casually since the previous fall. While the girl had been fine the girl's younger brother had been a student at the para-coastal elementary school, which had famously not been evacuated and lost 70% of its students to the tsunami. This had been all over the news, although it accounted for only 70 or so of the tens of thousands killed—that's how horrible it was. There's not even something funny in that story, マリ says, but also not anything especially meaningful. It had just been the confluence of many errors. And what could be said about the relation of her most recent boyfriend to the kid brother of his casual girlfriend? What even is that? And what was she to it? The boyfriend hadn't even been very close to this girl for having had a casual thing with her, his having spent that winter acting aloof and ignoring her messages, thinking himself older and more desirable than he was, masturbating frequently and beginning to worry his body would never fill out and harden. He had liked the drama of all of it and how he saw her. After the accident she still traveled to see him, to kiss him, to fuck him. For a few weeks she had even stayed in his house with a little moldering sleeping bag on his floor. It was this habit, of acting fine, needful even, when things were so obviously not fine, as rubble was still being cleared from the gutters of the inadequate seawalls of the razed town, as the story of the elementary school was being broadcast everywhere and literal statues of some of the children were being erected on the sealogged dirt where the school used to be, that had eventually disturbed the boyfriend. It got so bad he could no longer perform. And it took still another few years after that for him to understand what had happened, and who had broken up with whom, and why. When I ask why she's talking about him at all she explains that there's something important about the most recent person you've slept with. There is some sort of residue, she says, that's waiting to be washed off by the next thing. And it's so easy to read meaning into it.

I tell her I think the story is about ghosts. That he probably saw the brother's ghost and never told anyone, not even you. This makes her look at me.

People confessing to me makes me feel ill, and she had done it without warning. I hadn't gotten the proprioceptive goosebumps that usually impend confession—this had seemed less like a failure on my part than immense skill on hers. This whole journey out of the house had been due to her persuasiveness and agility—this obvious and devastating skill of hers seemed not abrasive but possibly redemptive, as though were I to follow her along far enough I might be born again. It reminds me of home, her commitment, her power. It stands, I think, in contrast to most of the people I have met recently, whose extreme aspects or characteristics appear to make them untouchable but not deific or hallowed. I imagine it is a little like the waitress watching the "variety" show on the small television. マリ seems good for me, somehow, like how a mother might say broccoli is good for me. Maybe I am sympathetic because she seems to want to write. Or because she spent the least amount of time during the long looping animated conversations before we went to the marine park in silence. But now she has confessed to me, and so sits in relation to everyone else who has impulsively done this: seen me mouth open on my knees. Is it because I look like I am willing to accept anything inside me? Do I not look sad, right now, in this cafe? Do I not look like anything?

Who are you texting, I'm asked. I have my phone unlocked, flat on the table in front of me, maybe even carefully arrayed, showing the three blue orphan messages sent to my boyfriend, weeks ago. The messages are small and innocuous, almost affectionate. マリ surely can't read them upside-down, but she sees the name, and she says it.

We spend the rest of the afternoon playing video games at her house. It's too hot to even think about going outside. Our matching bottles of soda are sweating over on the windowsill. At first we play colorful modern melee games, but I am so bad at them that I visibly start to appear upset, and she has us stop. Then for a long time I watch her play fast-paced puzzlers and rhythm games. A dating sim, then a city builder. By the mid-afternoon she has dug into her Steam library and found a game where you play as a floating flower petal in wind, then another where one plays an obscure occult card game with a largely unseen serial murderer in a haunted house. Then she puts on Braid, which was made by Jonathan Blow, and I watch her speed through the first two worlds, up to where she gave up when she first downloaded the game, back in 2016. There has been a new graphics update recently, a tenth anniversary edition, maybe, though largely it is the same and says little for Blow's dedication to his child.

Video games must have reached a far larger audience through those that watch them be played, as opposed to those that actually play them. This ability for distance, and the deliciousness of it, seems immediately culpable for many ails, and suggestive of a variety of theories of relation and affect and childhood development.

Where she gets stuck I help her, because I have seen how the levels in the third world are done in tutorials, but after that, we are on our own, because I haven't studied that far. We take turns, the lulling ambient music coming from all four of マリ's elevated surround-sound woofers and tweeters. Her keyboard has internal lights that sync with string LEDs on her walls and under the small sitting disk on which the computer sits.

In late afternoon I realize she's tricked me again. In my video research I learned that when Jonathan Blow was looking for music to include in his game he wanted long instrumental non-licensed tracks whose direction was unclear—whose structure was naturally cyclical and which would appear to a listener, even a careful one, to have no end and no beginning, and thus provide a disorienting comfort. She asks many questions that taste funny, like certain alkaloids or vitamins, and I answer them without shame, which feels genuinely but only distantly awful.